Faced with proof that they are engaged in mass crime and violence, corporations have a long history of denying evidence, blaming victims, complaining of witch hunts, attacking their critics’ motives, and otherwise rationalizing their harmful activities.

Denial campaigns have let corporations continue dangerous practices that cause widespread suffering, death, and environmental destruction.

Barbara Freese, an environmental attorney, confronted corporate denial years ago when cross-examining coal industry witnesses who were disputing the science of climate change.

She set out to discover how far from reality corporate denial had led society in the past and what damage it had done.

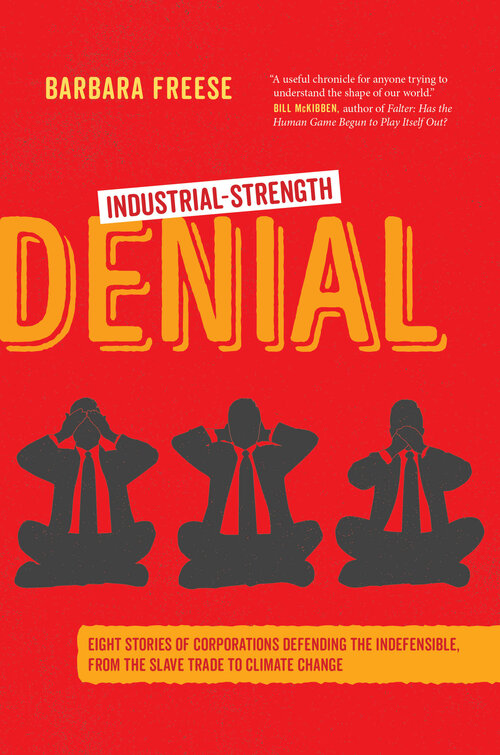

Her new book – Industrial Strength Denial (University of California Press, 2020) – is a tour through eight campaigns of denial waged by industries defending the slave trade, radium consumption, unsafe cars, leaded gasoline, ozone-destroying chemicals, tobacco, the investment products that caused the financial crisis, and the fossil fuels destabilizing our climate.

Examples of denial?

Slave ships are festive.

Nicotine is not addictive.

The kook behind the wheel caused the death, not the deadly car.

Why did Freese choose slavery to lead the book with?

“I knew there was a well organized abolition campaign in Britain in the late 1700s,” Freese told Corporate Crime Reporter in an interview last month. “I was curious – how did the industry respond to that? I knew from earlier readings, in particular Bury the Chains by Adam Hochschild, that the industry responded in an organized way. As it happens, much of that industry response was in little books or pamphlets that they published.”

“When you are looking at a corporate event, but trying to understand something about human nature, going back a couple of centuries doesn’t seem totally ridiculous. Then when I read these denials, they were so shocking and at the same time, they foreshadowed so much, that I decided it was worth including them in the book. And I thought nothing better could illustrate how far people could go, how strong the impulse to deceive and rationalize could be than people willing to do it in the face of this horrendous industry.”

What was their defense? How did they portray slavery as a good thing?

“They put forth a rescue narrative. They mischaracterized the experience of the Africans. They said that many of them wanted to be purchased and tried to market themselves. They described the crossing of the Atlantic as a festive experience, where they were singing and dancing and playing games on the decks of these ships. They said the conditions in the plantations were comfortable. They said the relationship between the slaves and their owners was like between children and parents.”

“They also then described how horrendous conditions were in Africa. They said that if they had not taken these people away from Africa, they would have met a terrible fate. They might have been killed during wars, or starved in famines, or they might have been sacrificed or eaten by cannibals.”

“They were able to portray things to a British audience, who had no idea what conditions were like in Africa or the Caribbean, in a way that made it seem heroic. They created this flip side narrative where abolition became an act of violence. They said that in order to protect Africans and not shut the gates of mercy on mankind, we had to continue dragging people away and enslaving them and their descendants.”

“They also did something we are seeing a lot now – they played up class divisions. They recognized that there were steep class hierarchies in Britain. They would argue that the slaves were way more comfortable than the poor in Britain. That was a way to make sure that the poorest people in Britain had more sympathy than the slaves. And they wanted to redirect the attention to the folks at home.”

“At the same time, they would ask – what if outside agitators would suggest to the sailor or the soldier or the peasant had equal rights with those higher in the class structure? They were suggesting that if you sought abolition for the slaves, you would be unraveling the class hierarchy in Britain.”

“They pulled out all of the stops. And given their power and their tactics, it is quite astonishing that the trade was ever abolished. And I’m talking about the trade, not slavery itself. That would come later.”

What’s the difference between the trade and slavery?

“The trade is going to Africa and getting the people who would be enslaved and bringing them and selling them to the plantations. There would be a period of time, a couple of decades, where slaves were still slaves, but they were not getting any new ones from Africa. That was true both in the British colonies in the Caribbean and in the United States.”

What was it about the abolitionist movement in the UK that helped them overcome the denial?

“They were actually very focused on evidence to the point where it just became so difficult for the industry to continue to deny it. The abolitionist would bring forth former sailors or doctors from the slave ships. They would bring forth the torture devices and the shackles.”

“They had an influential drawing of a slave ship to show just how crammed the people were below the decks. And eventually the brutality of this industry made it through. In that sense, it was quite a remarkable movement. It very clearly illustrated that the industry was lying and those protecting it were at the very least in denial.”

“One of the things I think is true, or maybe I hope is true, is that once denial is shown to be denial, the broader social denial can quickly erode. I’m hoping that maybe we are living through that moment now when it comes to police violence against African Americans and maybe when it comes to climate change.”

What about radium?

“Radium was discovered at the very end of the 1800s by Marie and Pierre Curie. All they knew was that it was incredibly powerful and it would burn human flesh. That’s something they discovered quickly. It ended up being used for cancer treatment. That made sense.”

And radiation is still being used to treat cancer.

“Not the way it was, but yes, it was the beginning of radiation treatment for cancer.”

“At the time, Europe was plunging into World War I. The radium industry as a private industry never took off there. The government was controlling the radium supplies because they wanted to make sure they had enough for cancer treatment. In the U.S., there was a battle – who should control the radium supplies? Congress tried to take them over, but a brand new company and industry was forming and they beat back government efforts to control the radium.”

“A new company – Standard Chemical – emerged. It was founded by Joseph Flannery. He discovers radium as something he could sell as an all purpose cure-all remedy. He needs some evidence that it’s good for treating things. He opens up a clinic – the first free radium clinic in Pittsburgh in 1913. People came in and they had radium injected into their bodies, or they would drink radium, or they would breathe radon gas.”

“When radium was used as a cancer treatment, you could use the same radium over and over. You would position it near the tumor and the tumor would eventually shrink if the treatment worked. But that wasn’t a good business model because you wanted more demand. That’s why it was important for Standard Chemical to promote the idea of internal radium consumption.”

“They were treating them not just for cancer, although they did treat cancer patients and killed many of them. But they treated people for arthritis, for high blood pressure, for anemia, which radium actually causes. From these humble beginnings, an industry sprang up where other people sold radium in a host of consumer products, radium drinks, radium cosmetics, radium pills. It became quite a trend.”

“One reason it worked so well was that this was a pretty innocent era when it came to radioactivity. People thought of it as a source of energy, a source of stimulation, like adding sunshine into your body.”

“This industry sprang up and lasted well into the 1930s. It was largely ended when one particularly wealthy high profile individual had been drinking radium and died a gruesome death which was well covered in the newspapers. Enough attention was brought to this industry that the demand disappeared. The federal government was starting to get involved, but they had limited authority.”

“Radium continued to be a consumer product. Radium paint would glow in the dark. The industry hired very young women, teenagers, and trained them to paint the glow in the dark paint onto watch dials and other products. They would put the paint brushes on their lips. That’s how they were trained to make a point with the brush.”

“They consumed a lot of radium and died gruesome deaths. Those deaths garnered attention in the 1920s. But perhaps because these were poor women instead of a rich man, their plight did not seem to hurt the market for radium as a cure-all. It wasn’t until this one industrialist died with lots of attention, that the industry pretty much faded away.”

Is there something about our society that makes us vulnerable to this kind of corporate denial?

“I think so. We want to believe we live in a just world. Psychologists study this notion of system justification. We want to think of our society as being just. And this is something that is done not just by people at the top of the hierarchy who are benefitting most from the system, but it happens among those lower in the system as well. It has to do with just preferring to live in a world that we perceive as just. We want to believe that our role in it is promoting something good rather than being surrounded by corruption and needing to fight that. That’s a painful thing to have to acknowledge.”

[For the complete q/a format Interview with Barbara Freese, see 34 Corporate Crime Reporter 32(11), Monday August 10, 2020, print edition only.]