How is it that William Proxmire came out of the same political economy in Wisconsin that produced the ultra-conservative Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy and went on to a career in the Senate of challenging corporate power, wasteful government spending and the military industrial complex?

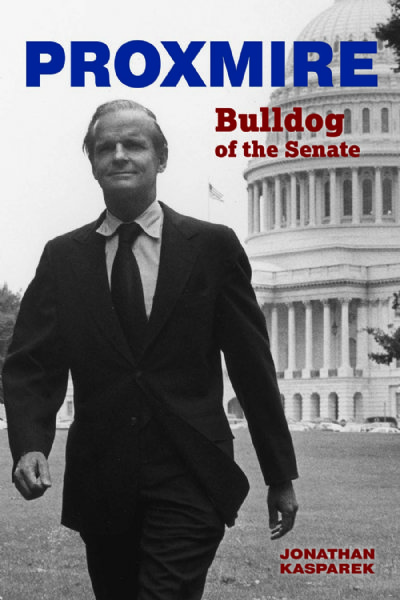

That’s a question raised by Jonathan Kasparek in his new book – Proxmire: Bulldog of the Senate (Wisconsin Historical Society, 2019).

One way was connecting with the people of Wisconsin on wasteful government spending.

Proxmire became nationally known for his Golden Fleece of the Month Award, given to a wasteful government program.

On July 10, 1981, Proxmire’s office put out a press release that opened: Senator William Proxmire announced Friday that “I am giving my Golden Fleece of the Month Award for July to the United States Army which spent $6,000 to prepare a 17-page document that tells the federal government how to buy a bottle of Worcestershire sauce.”

“Beginning in 1975, Proxmire and his staff had this idea of publicizing once a month an example of extraordinary government waste,” Kasparek told Corporate Crime Reporter in an interview last week. “It was the Golden Fleece Award for the worst federal expenditure. The first one, released in 1975, criticized a University of Minnesota study of why people fall in love. He later criticized funding for a Kalamazoo researcher on why people clench their jaws. He was able to make fun of these things. He picked amusing studies. He kind of did them a disservice by simplifying complex research. Both of those studies had legitimate scientific work, but on the surface appeared silly. He was able to capitalize on that to criticize federal spending.” (For a complete listing of Golden Fleece Awards, see Wisconsin Historical Society listing.)

But Proxmire also successfully challenged major government boondoggles, like the C-5A transport plane and the supersonic transport (SST).

“The C5-A was huge. He was the first Senator to make a big deal out of it. Eisenhower creates the phrase military industrial complex. But to criticize Pentagon spending at that time was dangerous. It was the Cold War. It was the Vietnam War.”

“This is a good example of how he differs from Bernie Sanders. He doesn’t rant and rave and denounce. He uses his position as Chairman of the Joint Economic Committee to hold hearings and lay out the evidence of how the aerospace industry is able to get these no bid contracts with guaranteed profits so the C-5A escalates from $1.4 billion to over $6 billion in a few years. And he opens the era where the Senate and House are willing to question Pentagon spending. It was no longer as risky. You are no longer going to be denounced as being soft on Communism or anti-war just because you question – why does the Pentagon need this new aircraft or this new weapons system? It was a turning point.”

What about his challenge to the SST?

“The idea was that the United States needed to build a super sonic transport airplane to compete with the Concord, which was being developed as a consortium between Great Britain and France. President Kennedy initiated federal spending to support research and development and eventual construction of the SST. Kennedy said – we are going to beat President Charles de Gaulle at his own game. We are going to show him that we can do this too.”

“Proxmire tried to remove spending for the SST just about every year. Kennedy started it, Johnson kept it going and Nixon kept it going. It was about pride. We have to have this. If the Soviet Union builds an SST, we need one too.”

“Proxmire was opposed to the federal government subsidizing private business for research and development. If there is profit to be made, they should be willing to invest themselves. If it’s not going to be profitable, why the hell is the United States government funding it? It’s only going to benefit a small number of people and the vast majority of citizens will never set foot on an SST.”

“Proxmire was eventually able to persuade enough people that the SST was cancelled in 1971.”

“One of the issues that did the SST in was the environmental impact. People were worried about the noise and the potential pollution from a supersonic jet. Proxmire pretty much single handedly brought it down.”

Proxmire would fly home to Wisconsin on his own dime to be with his constituents.

“In the 1950s, when he began running for Governor, he would go to factories at six o’clock in the morning and shake hands and chat with workers as they came into work,” Kasparek said. “He would go to Main Street and hang out at shopping centers, to meet people and talk with them. He would be at Badger games, at Brewer games, at Packer games. He was at the state fair. His goal was to meet lots of people to create a one on one connection, even if he talked to them for only a few seconds. That for him was critical. When he was out campaigning, he would do five or six campaign stops like that every day. He would sit in the back of a car and type out his own press releases on a little portable typewriter. Volunteers drove him around.”

“He would do stunts. In Superior and later in Green Bay, he would be on the radio by himself for 12 hours or more, just fielding calls and talk to whoever wanted to talk about politics. He had this ability to connect to people. And he liked meeting people who disagreed with him. They felt like he was a politician listening to them, rather than just talking with them.”

You report that he also worked odd jobs around the state. Like what?

“He worked on a trash collection crew in Fond du Lac. He worked on dairy farms. He worked in a factory canning peas. He worked in an electronic factory somewhere near Milwaukee. It was a way of keeping touch with working class voters. And it was good public relations too. He made sure the press was there working on the back of a garbage truck.”

Did he actually run around the state?

“He did. He was eccentric in this. He decided he was going to do a running tour of the state. Instead of being driven around by volunteers, he would have a route and he would run. And he would stop at every little town and talk to residents. He did it in the middle of winter also. He was running around the state in 1971 or so. There is a picture of him in the book in DeSoto, Wisconsin in December 1972 greeting a resident outside a post office. He is in his sweats running.”

Someone told me that the only money he spent on this later campaigns were postage stamps to return donations.

“In 1976 and 1982, the costs of his campaigns were simply the filing fees. He didn’t accept donations in the last two campaigns. By that point he was so well known and popular. He returned home to Wisconsin every weekend. He paid for his own flights home and volunteers drove him wherever he wanted to do. That was his campaigning. He would go out and meet people. He didn’t need to have a campaign the way we think about it today.”

[For the complete q/a format Interview with Jonathan Kasparek, see 34 Corporate Crime Reporter 10(11), March 9, 2020, print edition only.]