Every year, the federal government publishes its Crime in the United States report. That report deals primarily with street crime in the United States.

There have been calls over the years for the Justice Department to produce a yearly Corporate Crime in the United States report. But it has yet to do so.

To fill the void, academics and public interest groups have produced a handful of great, free corporate crime databases.

There is the Corporate Prosecution Registry at the University of Virginia Law School.

There is the Securities Enforcement Empirical Database (SEED) at NYU Law School.

There is the Violation Tracker at Good Jobs First.

And there is the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Clearinghouse at Stanford Law School.

Kristen Savelle is the managing director of the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford, where she oversees the FCPA Clearinghouse.

What have you learned from the database that strikes you as newsworthy?

“One thing that I find particularly interesting is the steep drop-off in new FCPA investigations disclosed in the past few years,” Savelle told Corporate Crime Reporter in an interview last week.

“When we talk about publicly disclosed investigations, we are necessarily talking primarily about public company investigations, because we typically learn about investigations in the SEC filings that are mandatory for public companies.”

“And yes, the number of public companies has declined in recent years, and maybe that decline explains the drop-off. But maybe not. We know that President Trump called the FCPA a ‘horrible law’ and that he allegedly asked administration officials to help kill the FCPA.”

“It is possible that both the SEC and Department of Justice have instituted fewer new FCPA investigations under the Trump administration, and that the drop-off in investigations will result in a drop-off in enforcement actions several years down the road.”

“Also, in recent years, the use of independent monitors has declined considerably, and in fact no action initiated and resolved this year required imposition of an independent monitor.”

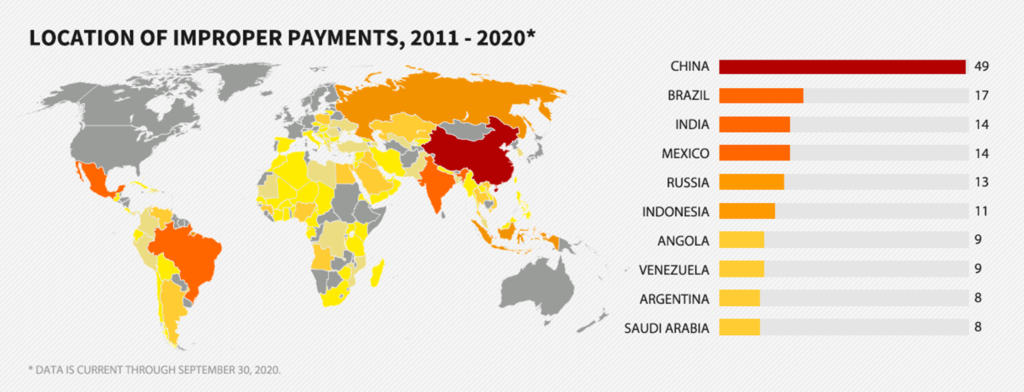

“In terms of the location of bribes, China has historically taken the top spot, but more and more actions are focusing on misconduct in Latin America.”

Is there evidence that the Trump Justice Department or SEC sought to suppress FCPA enforcement?

“No, I don’t have any evidence of suppression. All we know is that the number of newly disclosed investigations dropped considerably in 2018, and has continued to decline every year thereafter.”

Given that so few FCPA cases are brought every year against major corporations, what explains the FCPA’s outsized prominence and influence within the corporate criminal defense bar?

“I think a few factors may explain the prominence of the FCPA among the criminal defense bar.”

“First, and most importantly, is money. The number of enforcement actions filed is not necessarily indicative of the number of FCPA-related investigations pursued by companies or the government. At least 15% of disclosed investigations never result in an action filed – and this is almost certainly undercounting the actual number of SEC/Department of Justice investigations that never lead to enforcement, since we are relying only on investigations that are publicly disclosed in SEC filings.”

“These investigations can drag on for years and can be incredibly expensive for the target companies, and correspondingly lucrative for the law firms representing them. In fact, investigation costs can at times be many multiples of the sanctions that are ultimately imposed.”

“For example, the Wal-Mart investigation took 71 months. The investigative costs were $877 million while the sanction was $283 million accrued. That’s a cost to sanction ratio of 3.1.”

“Second, the jurisdictional reach of the FCPA is incredibly broad, and as a result a broad swath of U.S. and foreign companies and individuals are within the Act’s crosshairs.”

“The law applies to any company with shares listed on a U.S. exchange, including stock as well as American Depository Receipts – issuer, any company incorporated in the U.S. or with its principal place of business in the U.S., or any individual who is a citizen, national or resident of the U.S. – domestic concern, and to any company or person who engages in an act in furtherance of a corrupt payment while in the territory of the United States.”

“In practice, this means that foreign companies can be held liable for FCPA violations based on emails that are routed through the U.S., or based on money that passes through a U.S. bank.”

“Finally, the penalty for non-compliance can be steep, both in terms of penalties and in terms of ongoing compliance and reporting obligations. Plus there is the very real prospect of multi-jurisdictional enforcement.”

“The recent Goldman Sachs actions are a good example. The SEC and Department of Justice imposed combined sanctions of around $2.6 billion on Goldman, although some of that money will ultimately be paid to foreign regulators in connection with the resolution of foreign actions.”

Is there any evidence that enforcement of the FCPA over the years has deterred foreign bribery? Anyway to tell?

“I wish I had a good answer for you. I haven’t done any independent research into this question, and academics, practitioners and others have reached different conclusions.”

“Obviously it is difficult for outsiders to know for certain whether the FCPA actually prevented any specific instance of bribery.”

“The question then becomes, how do you measure the effectiveness of the law? Do you look at the number of enforcement actions over time, sanctions, how the government has fared when put to its burden of proof, the role and effectiveness of corporate compliance programs that may have been developed or enhanced in response to FCPA enforcement activity, changes to industry codes or standards.”

“The answer may depend on how you define effectiveness. At the very least, I believe the FCPA has prompted companies to focus more energy and oversight on compliance and internal controls.”

That’s fascinating about the costs of investigations sometimes being greater than the sanctions. Do you have numbers across the board for that or just the cases in the chart?

“We do not have investigation costs for all cases. Only a few companies disclose cost information, and those that do may not provide a complete picture of costs or may mix investigation costs with other related or even non-related expenses.”

“Walmart costs, for example, include investigation costs as well as costs for compliance reviews and for strengthening anti-corruption compliance programs – which can be considered part of the remediation – as well as costs to defend private lawsuits related to the FCPA investigation. Avon costs include costs for compliance reviews related to the FCPA investigation. We are constrained by what companies choose to voluntarily disclose in SEC filings.”

Do you capture monitors?

“We do capture the names of the monitors when disclosed in filing and settlement documents, but we do not conduct independent research to identify monitors and we do not publish this information on the website.”

You name names of prosecutors for each corporation in your database. Any chance you could name defense attorneys also?

“We do track this information in the database, but we do not publish it on the website.”

Do you have numbers on FCPA investigations triggered by voluntary disclosures, whistleblowers, newspaper reports and other categories?

“Yes. We capture the origin of investigations where disclosed by companies in SEC filings, and also the origin of enforcement actions where disclosed in charging and settlement documents.”

“The investigation origin tells us what the company considers to be the origin of the investigation and whether the company claims to have voluntarily disclosed misconduct to the SEC or Department of Justice.”

“The enforcement action origin, by contrast, tells us what the government deems to be the origin of the action, and whether the government is recognizing a company’s voluntary disclosure as a basis for awarding cooperation credit.”

“To find the investigation origin, go to the advanced search page – investigations dataset, and search for ‘origin of the investigation.’”

“Here is what I find in the database – voluntary disclosure: 169; anonymous tip/whistleblower: 17; press reports: 19.

“To find the enforcement action origin, go to the advanced search page – enforcement action dataset, and search for ‘origin of the investigation.’”

“Here is what I find -voluntary disclosure: 236; whistleblower: 12; press reports: 4.”

Is it your sense that voluntary disclosures are less common in the past few years? If yes, what explains it?

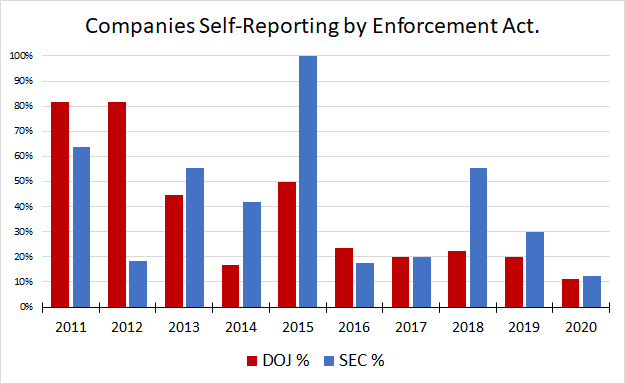

“It is somewhat surprising to me that voluntary disclosures have decreased so significantly in recent years, particularly disclosures to the Department of Justice.”

“In November 2017, the Department of Justice disclosed its Corporate Enforcement Policy, which was designed to encourage companies to voluntary self-disclose misconduct by providing more transparency as to the credit a company could receive for self-reporting and fully cooperating with the Department of Justice.”

“The policy does not appear to have achieved its intended effect, although there was a very minor increase in voluntary disclosure to the Department of Justice between 2017 and 2018.”

“Companies may simply be recognizing that a voluntary disclosure of potential FCPA violations can set into motion a wide-ranging sequence of events that will be far more costly to the company than any marginal benefit resulting from a penalty reduction for cooperation.”

“In fact, it is possible that the transparency afforded by the Corporate Enforcement Policy actually made it easier for companies to run a cost-benefit analysis comparing the potential advantages of voluntarily disclosing misconduct with the potentially enormous costs of investigating and resolving FCPA claims, and to make the calculated decision not to disclose.”

“Interestingly, we start to see more foreign firms sued starting in 2016, the same year we see a real dropoff in voluntary disclosures to the Department of Justice. Foreign firms are generally less likely to voluntarily disclose, and that may account for at least some of the decline.”

[For the complete q/a format Interview with Kristen Savelle, see 34 Corporate Crime Reporter 46(11), Monday November 30, 2020, print edition only.]