The September 2015 Justice Department Yates memo was widely seen as signaling a public move toward more prosecutions of corporate executives.

But does the Yates’ memo emphasis on individual culpability mean there will actually be an upsurge of prosecutions of corporate executives who oversee companies that engage in misconduct?

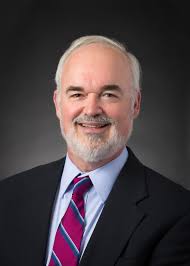

“The short answer is no,” says Wayne State Law Professor Peter Henning in a recent law review article titled Why It Is Getting Harder to Prosecute Executives for Corporate Misconduct. “One reason is that the new – or perhaps renewed – emphasis on pursuing individuals is not a real change in the Department of Justice’s policy. Prosecuting individuals has always been a priority, from the insider trading prosecutions in the 1980s of Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken, to the Savings and Loan Crisis in the early 1990s, to the accounting scandals that brought down companies like Enron and WorldCom in the early 2000s.”

“The companies were far less important than going after individuals, especially since the leader’s misconduct is what wiped out the enterprise,” Henning writes.

“Why the need for the Deputy Attorney General to defend the policy by proclaiming that federal prosecutors are not looking for ‘corporate heads’ when that appears to be its express purpose? Perhaps this is a means to set the groundwork for a handy excuse – to explain why companies might continue to receive the typical deferred – or non-prosecution – agreements to settle cases even though there are few individual prosecutions, and none involving senior executives. The oft-repeated insistence that pursuing cases against individuals is difficult because of the heightened intent requirements in many white-collar offenses reinforces this explanation.”

“This heightened intent helps to forestall criticism of the absence of prosecutions of high-level corporate officials,” Henning writes.

“Blurred lines of authority make it hard to identify who is responsible for individual business decisions and it can be difficult to determine whether high-ranking executives, who appear to be removed from day-to-day operations, were part of a particular scheme,” Yates said in 2016.

“In other words, do not blame us, it is the fault of these complex organizations,” Henning explained. “So despite the hope of generating more individual prosecutions, the Department of Justice seems to be hedging its bets at the outset—and for good reason. What is becoming increasingly apparent is that prosecuting cases against corporate employees and executives, which has never been easy, is getting harder. Nor is the Justice Department’s recent track record for pursuing individuals for corporate wrongdoing a harbinger of great success.”

As an example, Henning brings forth the track record in the Gulf of Mexico oil spill.

In 2011, Attorney General Eric Holder said “we must also ensure that anyone found responsible for this spill is held accountable. That means enforcing the appropriate civil — and if warranted, criminal – authorities to the full extent of the law.”

Henning found that four years later, the tally from the prosecutions of five BP Inc. employees – none a senior executive – was 23 counts withdrawn before trial, 23 more counts dismissed by judges, three guilty pleas to misdemeanors, and two acquittals.

“This track record does not inspire much confidence that prosecutors will be any more successful in pursuing individuals when there is serious corporate misconduct.

Henning says that “as companies get larger, there is a shrinking chance someone from the C-suite will have had any actual involvement in day-to-day decisions that provide the fodder for an individual prosecution.”