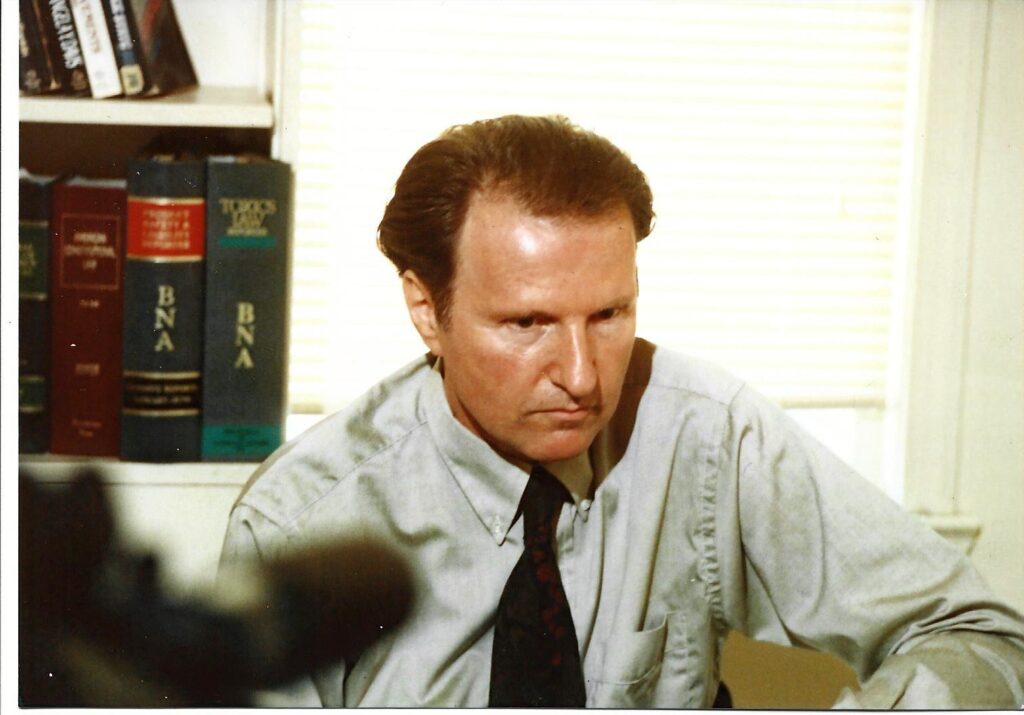

Rob Hager, public interest attorney and citizen activist who represented victims of corporate crimes around the world, died on July 3, 2025 at the age of 80 at his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

That’s according to an obituary in the August/September 2025 issue of the Capitol Hill Citizen.

Hager was born on October 21, 1944 in Buffalo, New York. His family moved to Mora, Minnesota, in 1954. He graduated from high school in upstate New York in 1962 and from Brown University in 1966 with a degree in American history.

He then went on to Harvard Law School, where he was on the Harvard Law Review and graduated in 1970. He went on to clerk for a federal court judge in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Hager spent several years working as an anti-corruption consultant in central Asia.

But most of his professional life was spent as an appellate litigator representing victims of corporate crime.

In Washington, he worked on the Ralph Nader for President campaigns, and when he moved to New Mexico, he became involved with the Green Party and with anti-nuclear politics, working with Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety.

But it was in his role as litigator for victims of corporate crime that he made his most enduring mark. In that role, he butted heads not just with corporate lawyers, but notably with trial lawyers who at the time were beginning to cut sweetheart deals with corporate defendants. Rob was one of the first public interest lawyers in the country to blow the whistle on the trial bar for shortchanging victims of corporate crime and violence.

In 1980, in the case Sholly v. Nuclear Regulatory Commissions, he won a key ruling from the D.C. Circuit finding that hazardous venting of krypton gas from the damaged Three Mile Island nuclear reactor was illegal.

He later co-founded the Nuclear Reform Project to help communities fight the nuclear industry. He was also a key part of the legal team representing the estate of nuclear and labor whistleblower Karen Silkwood before the U.S. Supreme Court, successfully organizing state Attorneys General around the country to support and win a $10.5 million Oklahoma jury verdict for the family.

In 1985, Hager traveled to Bhopal, India, to the Union Carbide chemical plant that leaked a deadly gas that killed thousands and injured tens of thousands. In an attempt to bring the victims’ lawsuit back to the United States, he helped organize the Bhopal Justice Campaign to raise awareness about the case.

Despite garnering prominent support, the effort was unsuccessful. The Supreme Court of India eventually approved a paltry $470 million settlement for tens of thousands of victims, many of whom would suffer debilitating illnesses over their lifetimes. Hager was opposed to quick settlements in major corporate crime cases.

“The problem with a quick settlement is that it comes at the expense of a just settlement,” Hager told Corporate Crime Reporter when he returned from India in 1985. At the time, Hager estimated that there were 3,000 dead as a result of the gas leak and more than 100,000 injured.

We asked Hager what he thought the damage estimate should be. “I came up with some- thing closer to $10 billion,” Hager said. “That’s more than the market value of Union Carbide. So, we’re talking about a settlement that would in fact transfer the ownership of Union Carbide to the people of Bhopal.”

After Bhopal came Agent Orange. Hager was offended by the dirty settlement cut by trial lawyers, corporate defense lawyers – all approved by a complicit federal judge. “A Brooklyn federal judge had in the early 1980s supervised a collusive class action settlement between several chemical companies who produced dioxin-contaminated Agent Orange and the lawyers he appointed to handle the class action lawsuit for some of the early injured veterans,” Hager wrote.

“In this settlement, the lawyers he appointed to represent the veterans got paid off, while the veterans got next to nothing.” “In return for allowing this miscarriage of justice, letting big chemicals companies off the hook for their negligence, the judge got a stash of millions deposited in a foundation he ran out of his court. This in itself was a violation of judicial conflict of interest law. But every case filed by Agent Orange veterans in any court anywhere in the country was sent to this judge, who was allowed by the appeals court to keep his monopoly over this corrupt deal.”

Hager rounded up a band of high profile appellate lawyers (including Harvard Law School’s Lawrence Tribe) to challenge the corrupt Agent Orange deal in the Supreme Court.

The legal issue presented to the Supreme Court in the Ivy case was whether the federal courts could interfere with the state court’s powers to try the veterans’ cases by shipping them all off to a single federal judge in Brooklyn.

In a remarkable organizing effort, Hager got all fifty state Attorneys General to file amicus briefs in Ivy, arguing that the vets had a right to make their case in state courts. Hager also sought to get the Clinton administration to weigh in on behalf of the veterans. Clinton refused, despite pleadings from many members of Congress.

The Supreme Court refused to hear the case and Hager blamed Clinton. “In my view, Clinton became personally responsible for the Supreme Court’s refusal to hear the case, which at the time was seen by me and other lawyers as the largest single injustice inflicted by the judiciary in American history,” Hager recalled. “That was the last straw for me with what I perceived to be the corrupt and careless Clinton administration, and the increasingly pro-corporate Democrats – who deserved to hear about it at the polls,” Hager wrote.

“If, with all his other flaws, Clinton was unable to make such a simple gesture of support for veterans who risked their lives supposedly to defend a constitutional system that they now sought to use, he did not deserve a second term.”

Hager realized it was time to build an alternative to the Democrats “who had become a sorry excuse for an opposition party to the right-wing Republicans.” He approached the one person he thought capable of tackling the nearly insuperable task of making a third party run. In 1996, Ralph Nader agreed to place his name on the California ballot, which at the time was considered a decisive state for Clinton.

The Green Party gave Nader its ballot line in 1996 in California. Green Party organizations in other states began organizing for Nader. Hager moved from Washington to Sante Fe where he was involved in the New Mexico campaign for Nader for President 2000. Rob Hager was a public interest lawyer who lived outside the non profit industrial complex. He had a laser focus on those workers and veterans and ordinary citizens under the boot of corporate power. He was in constant battle with the corporate duopoly of Democrats and Republicans that controls the judiciary and the country. He defended victims of corporate crime relentlessly – both in the judiciary and in the court of public opinion.

“Rob’s life was guided by a steadfast belief that systems, especially the judiciary, must work to protect human rights and ensure equality for all,” said Anou Borrey, a human rights expert and Rob’s partner of 22 years. “He was never concerned with how he would be remembered. What mattered to him was making a meaningful contribution to improve life for others. He took many risks in pursuit of that goal.”