The first year of the Biden administration was a down year for enforcement under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA).

In addition, for the first time since 2003, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Department of Justice did not impose any independent FCPA compliance monitors.

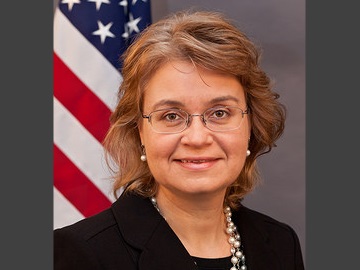

Kara Brockmeyer is a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton. She spent five years as head of the SEC’s FCPA unit.

“FCPA investigations have a long life,” Brockmeyer told Corporate Crime Reporter in an interview last month. “They are not the kind of cases you do in six months or even a year. On average, it’s somewhere between three and five years to investigate and bring that case.”

“The number of cases brought is a lagging indicator. The number of cases brought in the first year of this administration says a lot more about the prior administration.”

“People were expecting to see a fall off of cases at the beginning of the Trump administration. And we didn’t see a fall off of cases because they were basically drafting on cases opened under the Obama administration. Some of what we are seeing now during 2021 are investigations that were opened during the Trump administration or prior to the Trump administration.”

“I don’t think 2022 is going to see another historic low,” Brockmeyer said. “We are going to see the numbers come up. We are coming off of a number of years where we saw historic levels both in the number of cases brought but also the size of the penalties. There were some very large cases that were brought at the end of the prior administration, many of which were begun before that. They took a lot of government resources to bring.”

It’s not just the FCPA cases. Corporate crime cases are down across the board in 2021. But how would you compare the Biden administration staffing at both the SEC and the Department of Justice?

“It is clear that this is a less hospitable environment for companies and individuals caught in corporate crime investigations. You have seen that in the statements made by the new leadership at both the SEC and the Justice Department. We’ve seen it in the rollback of certain policies at the Department of Justice, including the rollback on the guidance regarding monitors and the return of the Yates memo view on what companies have to do when it comes to identifying individuals.”

“We have also seen very strong statements coming out of the new leadership at the SEC, including putting admissions back on the table for certain types of cases. We are going to have to wait to see how this plays out in the types of cases that they bring.”

That’s all rhetoric. But there’s little enforcement record to go on to prove the case.

“Yes. But what I would say is that it’s too early to tell. Even setting aside FCPA cases, which have a longer shelf life, the average SEC investigation of any type takes somewhere around two years. Everyone is going to be watching very carefully to see what happens in 2022. This is where we would expect to see an uptick in the level of enforcement activity.”

From your experience, what portion of FCPA cases are triggered by self-disclosures?

“It’s unfortunate that we don’t have the public data. The SEC and the Department of Justice don’t disclose that. Generally speaking, when I was at the SEC, we had publicly disclosed that somewhere between 25 percent to 35 percent of FCPA cases were the result of self-reports. And generally speaking, if you are a public company and making a disclosure to the SEC, you would make an immediate simultaneous disclosure to the Department of Justice. Those two units work so closely together that if you tell one it’s the equivalent of telling the other.”

Where do the other two thirds of the cases come from?

“The cases may come from a whistleblower. It may come from a news report. It can sometimes come from a referral from another international prosecuting or regulatory authority.”

“It can also come from an internal sweep. The Justice Department does those less frequently. But now, everyone is waiting to see what types of data analytics the government is going to bring to bear. There were a few sweeps that the SEC and the Department did when I was with the government. In one case it was a pharmaceutical sweep. But it was driven by the fact that the government had identified one or more pharmaceutical companies using the same agent that they had already identified as being problematic. That was just following the evidence and opening up the investigation wider.”

“The SEC did a sweep looking at investment advisers and asset managers – looking at how they were addressing anti-corruption risks.”

What can you tell us about the new Biden enforcement officials?

“At the SEC, the head of the FCPA unit is Charles Cain. He was the deputy of the unit under me. And he’s been running the unit for a long time. But the new leadership at the SEC – Chairman Gary Gensler and the director of enforcement Gurbir Grewal – have been public about their desire to be more aggressive in the corporate space. And we have seen that at the Department of Justice as well. We saw a number of policy changes that rolled back things that happened in the Trump administration.”

The boiler plate in SEC case settlements is that the defendant neither admits or denies the allegations. There was a push at the SEC to get defendant companies to admit. How did that admissions policy come about?

“The admissions policy dates back to when Mary Jo White was the chair and Andrew Ceresney was the director of enforcement. The idea was there were certain instances where it was not appropriate to allow the defendant or the respondent to settle an action on a neither nor deny basis.”

“There were certain instances where it was important either because of the nature of the crime or if admissions were being made in a parallel criminal investigation – a guilty plea for example. The feeling was that the defendant in the SEC action should have to admit at least the facts since they were admitting that in the criminal proceeding as well.”

“There were never a lot of true admission cases brought. It was going to be used in more serious cases. And admissions fell out of favor. We didn’t see people making admissions. The new leadership of the SEC has put it back on the table. They have said they will be doing it in appropriate circumstances. It is not something they will be looking to do in every case.”

There is no good way to judge whether FCPA enforcement is having an impact on foreign bribery. If it were like sports, we would have the numbers and we could figure it out. But what’s your sense?

“It would be interesting for an academic to look at that. I can tell you anecdotally that having been on the government’s side, including being involved in many international discussions and now being involved on the defense side, my sense is that there has been a significant impact on the level of corruption. Is it gone? No, unfortunately not.”

“But ten or fifteen years ago, when I started doing these cases, it was much more common for companies, especially foreign companies, to engage in this type of conduct.”

“You have seen significant changes in the international landscape. You have France going from not enforcing their foreign anti-corruption laws at all to now having the largest anti-corruption case brought – the case against Airbus. That does have a deterrent impact on companies across the board. It has absolutely had a significant impact.”

[For the complete q/a Interview with Kara Brockmeyer, see 36 Corporate Crime Reporter 6(12), Monday February 7, 2022, print edition only.]